- Login

- Home

- MABA

- MABF

- What's New

- Events

- Resources

- Biosolids Advocacy Fund

- Contact Us

|

May 2024 - MABA Biosolids Spotlight Provided to MABA members by Bill Toffey, Effluential Synergies, LLC SPOTLIGHT on Regional Biosolids Incinerators Incineration is a big deal for biosolids management in the Mid-Atlantic region. MABA’s May 7th lunchtime webinar “From Sludge to Solutions - Ashes to Ashes: The Benefits of Sludge Incineration” featured aspects of the role of incineration in current biosolid issues. Our region’s incinerators are in great shape, having accomplished upgrades foreseen by federal regulations promulgated in April 2016. Thermal processes have taken on a new glow of interest as a technology for destroying persistent organic pollutants, notably PFAS compounds. This checks the box on a list that includes concern for strengthened state-level regulations on soil phosphorus, storage, and the like. The role of incinerator owners in accepting trucked-in solids from neighboring WRRFs has added compelling value as agencies calculate among a variety of options the financial cost of replacing or upgrading solids-handling equipment. The Mid Atlantic has many notable sewage sludge incinerators (SSI). Of the estimated total regional production of 1 million dry metric tons of solids annually (dmt/a), 15 percent is incinerated. EPA’s 2022 ECHO (Enforcement and Compliance History Online) reports 47 public facilities in the region used sewage sludge incinerators (SSI). Two such SSIs, both serving as strong regional facilities, are the Multiple Hearth Incinerators (MHIs) operated by DELCORA (Delaware County (PA) Regional Water Quality Authority) and ACUA (Atlantic County (NJ) Utility Authority). DELCORA is the largest incinerator operation in the region, at 20,000 dmt/a. At 10,000 dmt/a, ACUA is the fourth largest facility. Between these two in size are the ALCOSAN (Allegheny County (PA) Sanitation Authority) Fluidized Bed Incinerators in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the Noman M. Cole Jr. Pollution Control Plant MHIs in Fairfax County, Virginia. The main stack for the DELCORA MHIs with the Regenerative Thermal Oxidizers and the Wet Electrostatic Precipitators Though both are multiple hearths operated by county authorities, several aspects of these two facilities provide distinctive contrasts. DELCORA Hauled Waste Program accepts deliveries of liquid sludges from municipal and industrial sources, blending and dewatering hauled waste with its primary sludge and WAS via gravity belt thickeners and belt presses to feed cake to the hearths. ACUA accepts only dewatered cake, which it blends with its own cake solids for feed to the hearths. Both facilities set the tipping price for sludges based on percent total solids, providing suppliers incentives to deliver consistent, well thickened residuals. Unless down for maintenance, DELCORA is operating both of its two MHIs 24-7, yet still has significant capacity. ACUA is only permitted to operate one of its two MHIs at any time, with reasonable incineration capacity in reserve. DELCORA is situated in a heavily populated community in Chester, Pennsylvania, with strong environmental justice commitments. ACUA’s MHIs are on an island, close to a cluster of public utility operations (the WRRFs, the county operated municipal waste landfill (6 miles away), and an on-site wind generator farm) with its closest “receptors” a neighbor known as Venice Park and a self-storage facility, with a long distance to the city and resort developments.

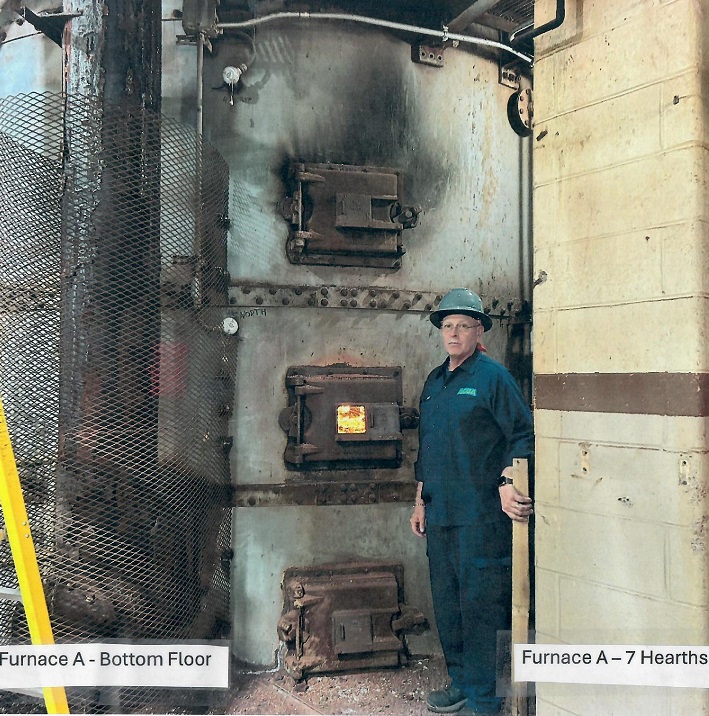

Bottom Floor at ACUA Furnace A with 7 Hearths Both agencies share significant issues. Foremost is the special challenge of heightened state regulatory vigilance over incinerator operations. MHIs have, as an inherent safety measure in operations, emergency bypass of air emissions controls in the event of a power loss or dip. Under its EPA Consent Decree, ACUA is penalized $3000 by EPA Region 2 each time it has such a bypass caused by Atlantic Electric. Vice President Joe Pantalone says that in each of 2020, 2021 and 2022 ACUA reported 17 bypasses. He believes it would be reasonable and fair to have EPA allow at least a once-a-quarter “mulligan,” however EPA has held to its no-tolerance condition. DELCORA, too, has faced regulatory scrutiny for its MHI bypasses. Its issue with bypasses was amplified by several factors. The “transparency” policy under its environmental justice program obligates DELCORA to report to its citizenry each bypass occurrence, and it seeks to minimize the number of reports. Electric power from PECO comes to DELCORA in two separate service lines, and an unannounced switch from one line to the other, even for a matter of several seconds, is sufficient to result in a shutdown and a reportable bypass. The electric company has provided no solution to this seconds-long interruption, and, therefore, DELCORA has now installed a large uninterruptible power supply (UPS) battery trailer, at a cost of one-half million dollars, to cover the occasional three second gap. ACUA has been also considering a major upgrade to its UPS system to similarly manage emission control interruptions and will be looking for financial assistance with this as it renegotiates its operations agreement with the wind farm operators. Air pollution control equipment and compliance with air permit standards drives a large part of the biosolids management focus of both agencies. When the new SSI regulations were promulgated, fugitive emissions were the big compliance challenge for ACUA. The agency was compelled to install a fugitive ash capture system at a cost of over $3 million, and it recently overcame an issue by now achieving mandatory pH levels in its scrubber water. In design are new scrubbers and ID fans for both MHIs. ACUA is in continuing discussions regarding the EPA position on imposing installation of continuous monitors for mercury, about which the Consent Decree made no mention. DELCORA had big challenges, too, with compliance monitoring. DELCORA’s Director of Operations and Maintenance, Mike Disantis, credits unimpeachable collaboration among key champions from operations, maintenance and permit sections for overcoming seemingly unsolvable compliance challenges. For Irene Fitzgerald in Permits, the challenge was in making a compelling case for the risks of Title V Permit noncompliance. To make the case, she had to master combustion chemistry -- the role of overfeeding of solids to incinerator temperatures, the causes of slagging and cyanide and hydrochloric acid formation, and the importance pH control, to name a few -- to help Operations and Maintenance. Operations Supervisor Tommy Czwalina, who had previously operated the furnaces, used his style of gentle probing, patience and strategic suggestions, to work with operators who had many more years of service than he, but who had varying operations practice. He had to overcome the undesirably wide variability in cake solids in the MHI feed, including issues of mixing, thickening, polymer addition, and press operations. Automation and Electrical Maintenance Manager Clint Swope discovered clever solutions, such as monitoring voltage to identify fouling of electrodes in the ESP precipitators, recognizing the effect of sudden grease influx on excessive temperature spikes in the RTO, and developing a creative method of cleaning the belt press filters with sprays of hot water. With the support of Executive Director Bob Willert and the Board of Directors, Clint was rewarded for his ingenuity by receiving minimal pushback when he made the equipment purchase request. Control Room with SCADA and Video Screens for MHIs at DELCORA As with DELCORA, ACUA is moving toward a “cleaner” incinerator operation that arises with upgraded consistency of sludge feed quality. ACUA is totally revamping its means of receiving outside cake, with construction of a new receiving area with at-grade hoppers, as sludge providers deliver cake ranging in percent solids from 16% and 29%. ACUA will have two 60-yard hoppers where today it only has one, so it can better manage the blending of outside sludges of low percent solids with sludges of higher solids before pumping the mixture to the top of the furnace.

ACUA Furnace A at the Electrostatic Precipitator A major payback to DELCORA and ACUA in their keen focus on incinerator operations and compliance is their capacity to serve a wide variety of public agencies in the region with biosolids disposal services. For ACUA, solids from some agencies are delivered on dependable schedules, while others call upon Pantalone when they have unanticipated interruptions in their other outlets; over one six-month period cake came down from Connecticut after a major facility in Stamford went out of service. DELCORA also has a robust panel of suppliers and are often fully subscribed. Both facilities may find themselves players in the PFAS disposal arena. PFAS has increased interest in incineration, as the operational temperature of upgraded SSIs are believed to have the potential to accomplish PFAS destruction. In ACUA’s case, with one incinerator not in service, ACUA could take steps to allow its second incinerator to operate concurrently, should incineration be proved a viable method for the destruction of PFAS. This could present a business opportunity for the Authority. Against this uncertainty in demand for biosolids incinerations services is the parallel opening of biosolids composting services within the same market area. DELCORA and ACUA provide important lessons. Though unknowns and contingencies in the biosolids marketplace will likely persist, the availability of multiple new “merchant” disposal outlets is a turnaround in the biosolids market within the MABA region which hasn’t been enjoyed for many years. The stories of ACUA and DELCORA reaffirm the importance of strong champions within each agency to accomplish impeccable operations, even in the face of what at first blush are unreasonable expectations, innovative technologies and complicated regulations. For more information, contact Mary Firestone at [email protected] or 845-901-7905. |