|

Biosolids NewsClips - February 2, 2026

This month’s NewsClips highlights how biosolids programs are being reshaped by increased PFAS scrutiny, public engagement, and emerging treatment technologies, and how utilities and communities navigate risk, innovation, and evolving regulatory expectations throughout the Mid-Atlantic and beyond.

MABA Region

Environmental concerns surrounding PFAS and legacy contamination continue to dominate the news in the Mid-Atlantic and beyond. Biosolids planning and innovative solutions explored or implemented by utilities and industry partners are met by opposition.

Across the region, there are multiple articles from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia that focus on PFAS and highlight the level of attention that biosolids programs are facing in the coming year. It bolsters the need for industry partners to foster collaborative and strategic efforts that work toward solutions.

National News

Nationally, there is a lot of news coverage on items near and far. Here are a couple of the more positively focused articles. In Illinois, the first U.S. Hemp-Biosolids field trial examines how EPA-approved biosolid fertilizer can support regenerative agriculture and sustainable hemp cultivation in the United States. In Tennessee, Spring Hill is hosting a “Name-A-Trailer” contest to find the four best sludge truck names for the city’s new sludge-hauling trailers.

International News

Internationally, there are multiple projects that share a glimmer of progress. In Germany, Mannheim’s wastewater treatment plant is piloting a project that transforms sewage gases into green methanol, a cleaner, nearly-carbon-neutral alternative to heavy fuel oil. Italy has inaugurated its first integrated district heating and cooling system powered entirely by biogas generated from sewage sludge, marking a significant step toward large-scale circular energy models. In Ireland, they are collaboratively seeking ways to extract useful materials from wastewater sludge that can be reused in a way to help reduce the steel industry’s emissions.

MABA will continue to monitor these developments and provide timely updates to members.

If you have biosolids-related news to share or are interested in participating in MABA’s Communications Committee, please contact Mary Baker at 845-901-7905 or [email protected]

Biosolids News

(as of January 14, 2026)

MABA Region

Virginia communities push back against sewage sludge on agricultural land as PFAS concerns grow

Richmond, VA (24 Nov 2025) - As state Sen. Richard Stuart, R-King George, said in a recent State Water Commission hearing, “we don’t want it to go in the river anymore, for goodness’ sake.” Biosolids can contain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which pose serious health risks if people are exposed to them in higher amounts. The danger has led some states to outright ban, or enact stricter requirements in the use of biosolids, and prompted calls from some Virginia communities to do the same.

Two more New York towns take action against the spreading of biosolids

Albany, NY (3 Dec 2025) - Two more New York towns have taken action in the last month against sewage sludge as state legislation to put a moratorium in place failed to pass earlier this year. The towns of Guilderland, in Albany County, and Goshen, in Orange County, both enacted local laws that ban the spreading of sewage sludge on farmland, joining other local municipalities and counties across the state. Sewage sludge is what's left over in the wastewater treatment process and has been applied to farmland as a fertilizer for decades. However, there are now concerns about the contamination of soil and water with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that surround these spreading sites.

Guilderland adopts moratorium on sale or use of sewage sludge

New York Farm Bureau calls for state to test sewage sludge for PFAS

Albany, NY (5 Dec 2025) - The New York Farm Bureau will oppose the land application of contaminated sewage sludge and encourage testing prior to spreading, a change from their supportive position last year, the organization announced Friday. The lobby group recently held its annual convention, which included representatives from county farm bureaus across the state. Part of the convention is spent voting on policy positions for the upcoming year. Sewage sludge is the end of the wastewater treatment process that can then be applied to farmland as a cheaper form of fertilizer.

Farm Bureau reverses stance on sewage sludge use

New York Farm Bureau says no more ‘sewage sludge’ used as fertilizer unless tested, cleared of PFAS

How Homeowners Can Build Greener Lawns With Smarter Fertilizer Choices in 2025

Annapolis, MD (4 Dec 2025) - Most of us want that deep, resilient green lawn, but we don’t want to waste money, harm waterways, or babysit turf all summer. In 2025, smarter fertilizer choices help us do all three. We’ll show how to read your yard like a pro, pick greener products that actually work, and apply with precision so nutrients end up in blades, not the storm drain, especially if you’re using liquid lawn fertilizer, where even coverage and correct dilution make a bigger difference than people expect. If you’re curious why this matters beyond the curb, see the EPA’s overview of nutrient pollution for the bigger picture on runoff and algal blooms. Let’s get your lawn, and the local watershed, thriving.

DEP says Schuylkill County biosolids company broke environmental rules

Pottsville, PA (8 Dec 2025) - The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection has notified a western Schuylkill County biosolids company that its operations repeatedly broke state environmental laws and violated the company’s permit, the department confirmed on Monday. Tully Environmental, which does business as Natural Soil Products Inc. in Frailey Township, stored far more biosolids on site than it was allowed to, failed to conduct required groundwater sampling in coordination with DEP as required, and used unapproved testing methods during its most recent sampling event, the department said.

Northampton County continuing stand against deep injection

Eastern Shore, VA (10 Dec 2025) - In his final County Administrator’s update before retirement, Northampton County Administrator Charlie Kolakowski briefed the Board on recent conversations with officials in Orange County, including a supervisor there who raised concerns about biosolids regulation and PFAS—commonly known as “forever chemicals.” Kolakowski said Orange County officials described what they view as a significant regulatory gap: no agency currently conducts routine testing of biosolids for PFAS or similar contaminants, and responsibility for oversight is often passed between state and federal entities. As a result, farmers and landowners lack clear information about what substances are being applied to their fields.

Orbital Biocarbon secures key investment to grow biosolids solution

Washington, DC (10 Dec 2025) - Sludge disposal company Orbital Biocarbon announced a funding round led by Toby Z. Rice, who is president and CEO of EQT Corp. and was a seed investor in Archaea Energy before it was sold to BP for more than $4 billion. The deal allows Orbital to ramp up development of its sewage sludge processing facilities, which use a form of pyrolysis to turn dried sludge into biochar. The company currently has one facility in development in the Pittsburgh area which it projects will be commercially operational by mid-2027. But the new investment round will allow Orbital to pursue multiple projects at once in states from Pennsylvania to Maine.

DEC Issues Suite of PFAS Response Actions and Resources to Protect Communities

Albany, NY (12 Dec 2025) - New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) Commissioner Amanda Lefton today announced a suite of significant new actions and helpful resources to protect, educate, and assist New York communities in addressing the ubiquitous threat of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contamination. DEC launched a new progress report detailing New York State’s leadership in addressing PFAS; released a new study detailing the widespread presence of PFAS on the landscape; finalized important wastewater treatment plant guidance that protects drinking water and other surface waters; proposed new policies directing DEC’s actions in PFAS investigations and sampling of biosolids products; and launched a new webpage – dec.ny.gov/pfas – that provides a one-stop resource about these and other initiatives and information about DEC’s multifaceted efforts to address PFAS.

State DEC proposes updates to biosolids guidance, other PFAS regulations

New York may require composters using biosolids to test for PFAS

PFAS contaminants ‘here for the long haul’—DEC issues new guidance, policies on ‘forever chemicals’

New York’s PFAS plan: targeting “forever chemicals” in wastewater, biosolids

Pump demolition, new installation approved

Watertown, NY (11 Dec 2025) - Wastewater was a hot topic in Tuesday’s Public Works Commission meeting, leading to two approvals starting with a work order for new primary sludge pumps.Since the sludge system cannot be shut down completely, replacements will occur in a planned sequence to maintain operations. Additional work — such as existing pump concrete base removal and piping adjustments — will be performed by contractors to ensure the new pumps integrate properly with the existing system layout.

The Impact of PFAS ‘Forever Chemicals’ on Edible Crops, Food Quality

Albany, NY (22 Dec 2025) - A researcher in the University at Albany’s College of Nanotechnology, Science, and Engineering was awarded nearly $420,000 from the National Science Foundation to study how the accumulation of toxic “forever chemicals” in edible plants impacts food quality and safety. “Studying the uptake and distribution of PFAS in edible plants, especially in parts that strongly accumulate PFAS mass, is essential for evaluating the potential health risks associated with consuming PFAS-contaminated crops,” the project summary reads. “Understanding the dynamics of PFAS in soil-plant systems is also critical for developing regulatory standards to protect public health and the environment.”

Right to Farm or Right to Poison?

Albany, NY (1 Jan 2026) - The practice of spreading sewage sludge on agricultural land has gone on for decades, based on the premise that sewage provides a suitable fertilizer and a means to recycle waste. It reads like a plausible win-win solution, but recent studies indicate sewage sludge contains serious pollutants that can convey into food produce via cropland spreading, and even via home and community gardens that utilize certain fertilizers, euphemistically called “biosolids.”

New year, new environmental battles brew in Chesapeake Bay states

Mayo, MD (12 Jan 2026) - Several other bills are also in play. PFAS: The Potomac Riverkeeper Network is pushing legislation that would require setting interim safety standards for toxic PFAS in biosolids, test biosolids (sewage sludge) for the chemicals and establish a protocol for disposing of contaminated biosolids. Many farmers use biosolids to fertilize their fields, and biosolids containing PFAS are making their way from Maryland to Virginia farm fields and raising health concerns.

Nationally

Adverse Court Decision in Toxic Sewage Sludge Case Now on Appeal

Washington, DC (25 Nov 2025) - Today, Plaintiffs appealed a decision by a federal district court in a case challenging the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) failure to identify and regulate toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in sewage sludge sold as fertilizer. High levels of PFAS in land-applied sewage sludge, also referred to as “biosolids,” are contaminating farmlands, livestock, crops, and water supplies and endangering human health across the country.

Biosolids/Clean Water Act: Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility Appeal Dismissal of Citizen Suit Action Alleging EPA Failure to Address PFAS

US landfills emit nearly a ton of airborne PFAS a year, study finds

Washington, DC (25 Nov 2025) - US municipal landfills leak roughly 1,800 pounds of PFAS into the air annually — evidence that the country’s garbage dumps are a persistent source of airborne “forever chemicals,” according to a new nationwide study. Researchers from North Carolina State University (NCSU) and Oregon State University (OSU) measured levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in gases emitted from 30 municipal landfills of varying ages across the US. Most of the PFAS found were a specific type called fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs), which are produced when common PFAS-based water repellent coatings on household items, including stain-resistant carpet and couches or waterproof rain jackets and boots, slowly break down.

A celebrated conservationist’s unwitting role in Maine’s PFAS crisis

Unity Plantation, ME (1 Dec 2025) - Conservationist Bill Ginn is mad about what happened at the heavily contaminated Hawk Ridge Compost Facility that he started here 35 years ago as a recycling center. He sold it three years after he started it. Since then, three large waste management companies have owned it, most recently Casella Waste Systems. Now the largest composting facility in the state, Hawk Ridge has processed 150,000 dump trucks worth of mostly papermill solid waste since 1989. Extensive PFAS contamination on and around it forced the company to announce it will close the facility by June of next year.

Early study results show landfill liquid in Wisconsin has high PFAS levels

Madison, WI (1 Dec 2025) - Early results of a new study show liquid captured at landfills contained the highest levels of PFAS among liquid wastes sampled statewide in Wisconsin. Since 2023, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have been collecting and analyzing samples from four waste materials that could be potential sources of PFAS in groundwater, which provides drinking water to two-thirds of state residents. It’s also a source of drinking water for around 800,000 private wells.

First U.S. Hemp-Biosolids Trial Tests Breakthrough Sustainable Fertilizer

Champaign-Urbana, IL (2 Dec 2025) - A first-of-its-kind U.S. field trial is underway to explore how Class A biosolids can be used as a sustainable fertilizer for industrial hemp grain and fiber production. Led by Dr. D.K. Lee and a team of crop science researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, in partnership with The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD) and Flura, Inc. (Flura), this research, officially titled "Evaluating Environmental Benefits of Growing Hemp with Biosolids" examines how EPA-approved biosolid fertilizer can support regenerative agriculture and sustainable hemp cultivation in the U.S.

Researchers Launch U.S. Trials Testing Biosolid Fertilizers on Hemp

Homegrown Innovation: Pittsburgh-rooted startup Flura leads national breakthrough in sustainable biosolid fertilizers

Orofino City Council approves contract with J-U-B for engineering biosolids storage plan

Orofino, ID (3 Dec 2025) - At their meeting Nov. 25, Orofino’s City Council approved a contract with J-U-B for engineering a temporary biosolids storage plan, scope and costs. For a number of years, the city has sent biosolids from the Wastewater Plant to Kamiah where it was spread on farmer’s fields. Kamiah notified the city several months ago that they would not take them after Jan. 1, 2026. Since that time, Water/Wastewater Supervisor Michael Martin has been working on options, including building the equipment inhouse to process the biosolids into food grade that could be stored or put anywhere. He and his staff have also been looking at where they can store the biosolids until that equipment is ready and approved by DEQ (Department of Environmental Quality). One of those storage options is leasing a piece of property from the county.

San Miguel CSD prepares to remove decades of ‘sludge’ from wastewater ponds

San Miguel, CA (4 Dec 2025) - Months after the Machado Wastewater Treatment Facility received approval for a $54 million expansion, the San Miguel Community Services District (CSD) is preparing to clean up more than 20 years of accumulated sludge to prepare for the upgrades. For nearly two decades, two of the facility’s four treatment ponds have collected sludge without any full-scale removal. “As the solids accumulate in the ponds, it reduces efficiency, reducing the plant’s ability to break down additional solids,” San Miguel CSD General Manager Kelly Dodds explained in an email to New Times. “If the solids levels are allowed to build too much, the solids start carrying over in the plant effluent, affecting the effluent quality.”

Agreement helps wastewater

Oxnard, CA (5 Dec 2025) - The Council, on Tuesday, December 2, approved an agreement with Carollo Engineers for construction management and inspection services for the primary clarifiers and sludge improvement project. Assistant Director of Public Works Tim Beaman presented the item and noted it’s the second project presentation. The agreement is for an initial term of three years, from December 2025 through December 2028, plus two one-year terms ending December 2, 2030, totaling $3.782 million, for construction management and inspection services. The 2017 Master Plan identified the primary clarifier and the activated sludge upgrades as high-priority projects, and he said the primary clarifier was built in 1975, and had exceeded its useful life by 25-30 years.

Drying biosolids in summer pays off for Cashmere

Cashmere, WA (7 Dec 2025) - It is nobody’s favorite topic at the dinner table, but the way Cashmere handles what goes down the drain is saving the city tens of thousands of dollars a year. At the Nov. 25 City Council meeting — with Mayor Jim Fletcher presiding and councilmembers Jeff Johnson, Chris Carlson, John Perry, and Jayne Stephenson (via Zoom) in attendance; Councilmember Shela Pistoresi excused — staff reported that the city’s new hybrid approach to managing wastewater “biosolids” cut hauling costs by an estimated $50,000 this year. Director of Operations Steve Croci, Treasurer/City Clerk Kay Jones, and Wastewater Services Manager Dorien McElroy were also present.

Monterey One Water launches food waste receiving and co-digestion program

Monterey, CA (8 Dec 2025) - Monterey One Water, Monterey, California, hosted a ribbon cutting ceremony Dec. 2 to celebrate the launch of its food waste receiving and co-digestion program at its Marina, California, facility. The project converts food scraps into renewable energy and is expected to divert up to 51,000 tons of organic waste annually. Burlington, Ontario-based Anaergia Inc. partnered with Monterey One Water to provide and modify anaerobic digestion technology at the facility. The modifications now allow Monterey One Water to receive and co-digest food waste in existing digesters used to process wastewater biosolids, resulting in the production of more biogas, which can be used in linear generators or converted into renewable natural gas (RNG).

PFAS in Michigan agriculture

East Lansing, MI (9 Dec 2025) - PFAS have entered farmland through several different pathways including land application of materials containing high levels of PFAS, such as biosolids, paper sludge and tannery waste. Other pathways include irrigating with contaminated water and potentially through the application of pesticides, herbicides, septage and precipitation, although more research is needed to understand the extent of soil contamination resulting from these pathways.

Company appears to have given up on Mount Perry biosolids storage lagoon

Perry County, OH (10 Dec 2025) - With little fanfare, a company that had been planning to build a controversial storage facility for “biosolids” in Mount Perry apparently abandoned the project earlier this year. In response to an inquiry from The Perry County Tribune, a spokesperson for the Ohio EPA confirmed that the permit for the project, which had been under appeal by a local citizens’ group, was canceled eight months ago. “On April 7, 2025, at the request of Mt. Perry Nutrient Storage, LLC (Quasar Energy Group), Ohio EPA terminated the NPDES permit for the Mt. Perry Nutrient Storage Facility,” reported Bryant Somerville, press secretary for the agency.

Zionsville Sewage Crisis: Town Ignored 20 Years of Warnings

Zionsville, IN (10 Dec 2025) - The Zionsville Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP), nestled near Starkey Park and the Rail Trail, is currently operating at a capacity it was never designed to handle. This crisis is leading to environmental contamination risks, severe odor problems, and significant public safety hazards. Critics are calling for immediate intervention, demanding the town halt a costly $21.5 million expansion and instead pursue the regional solution its own planning documents have long recommended.

PFAS/Sewage Sludge Incinerator: Conservation Law Foundation Files Challenge Before U.S. EPA Environmental Appeals Board Addressing Manchester, New Hampshire NPDES Permit

Manchester, NH (11 Dec 2025) - The Conservation Law Foundation (“CLF”) filed a Petition for Review (“Petition”) of the City of Manchester, New Hampshire’s Clean Water Act National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) Permit before the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) Environmental Appeals Board (“EAB”). The Petition was filed before the EAB since the Region 1 Office of EPA issued the NPDES Permit. Manchester is stated to operate a wastewater treatment plant (“Plant”) which is described as Northern New England’s largest wastewater treatment facility.

Could the city sell the landfill?

Sault Ste. Marie, MI (12 Dec 2025) - Big changes could be coming to the city-owned landfill in the next year to 18 months. Mayor Matthew Shoemaker said the city might end up selling the landfill or searching for a partner to help run it if other levels of government don’t step up with funding. Expanding the landfill, which is necessary in the next seven years, as well as adding facilities for biosolids and organics could cost between $150 and $200 million, Shoemaker said.

Hot Springs wastewater plant getting new sludge process

Hot Springs, AK (16 Dec 2025) - The city reported a more than $2.7 million balance for contingencies that may arise from its $68 million project to close out the consent decree its wastewater system has been under for more than a decade. The city said the balance presumes contracts yet to be issued will be awarded within budgeted amounts. The more than a dozen contracts the $68 million in bond proceeds are financing total $65.2 million, which includes projects yet to be bid.

Largo commission approves major wastewater, public works projects

Largo, FL (16 Dec 2025) - The Largo City Commission recently approved two capital projects totaling $10.5 million aimed at improving the city’s wastewater treatment and public works operations. During its Dec. 2 meeting, the board unanimously approved a four-year, $10 million contract with a national firm to treat and remove the city’s wastewater biosolids. The move comes as Largo’s current biosolids facility deteriorates after decades of use. Wastewater Manager Kyle Hicks told commissioners the facility was built in the 1970s, with equipment installed between then and 1991.

30,000 gallons of sludge dumped in Oakland neighborhood sewage spill: KDHE

Topeka, KS (17 Dec 2025) - Kansas health officials say around 30,000 gallons of sewage was released into Topeka’s Oakland neighborhood near the start of December from a local water treatment plant. The Kansas Department of Health and Environment issued a report on Dec. 17 outlining its findings in the aftermath of a sewage spill at the Topeka Wastewater Treatment Plant located at 1115 NE Poplar St. The spill occurred on Dec. 6 and resulted in a big mess for the city’s Oakland neighborhood.

DeSoto County commissioners approve compost facility after threat of legal action

Arcadia, FL (17 Dec 2025) - DeSoto County commissioners approved a controversial compost facility on Tuesday after months of heated public debate and legal challenges. In a 3-2 vote, commissioners accepted a mediation agreement with Osceola Organics to allow the company to build a biosolids processing facility on State Highway 70, near the Manatee County line. The facility will convert treated sewage into agricultural-use fertilizer, according to the company.

Sludge being placed on farmland coming back to Desoto County

Lynnwood plans massive sewage plant rebuild; Edmonds neighbors say they were caught off guard

Lynnwood, WA (25 Dec 2025) - Tucked away in a ravine along Puget Sound in an annexed portion of Edmonds, the City of Lynnwood’s Wastewater Treatment Plant has quietly done its job for more than six decades. Now, City officials say it’s time for a full reboot. Lynnwood is planning a decade-long overhaul of the plant, a project now estimated at about $330 million, to replace worn-out equipment, accommodate population growth and comply with stricter environmental rules. The upgrade would reshape how wastewater from Lynnwood and parts of Edmonds is treated before being discharged into Puget Sound.

In This St. Augustine Community, Residents Fight to “Stop the Stink”

St. Augustine, FL (29 Dec 2025) - Since moving to Morgan’s Cove, a single-family home community in St. Augustine, Florida, in 2022, Babcock and dozens of other residents have been affected by an odor they’ve described as “putrid,” “unbearable,” and even an “assault on our senses.” It’s not a hidden cow pasture, and it’s not dog poop. It’s the nearby processing of biosolids — defined by the U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as treated sewage sludge “intended to be applied to land as a soil conditioner or fertilizer.” Smells come from what’s inside the biosolids: compounds such as mercaptans and ammonia and elements like sulfur.

Urban Waste, Rural Consequences

Crescent City, FL (29 Dec 2025) - But before long, the Simoneauxes got a disturbing surprise, one not likely to have happened in their former urban home. In 2021, Volusia County resident Laurence Downes applied to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) under the business name Jennigirl for a permit to spread biosolids in Putnam County. Downes also owns American Bioclean, a waste management company that cleans out septic tanks in east Central Florida.

The Price of Poop

Gainesville, FL (29 Dec 2025) - Every year, human waste, or, in regulatory language, biosolids, leaches into its waters. South Florida governments have largely banned the practice of spreading biosolids on farm fields, leaving rural communities in North Florida to deal with the consequences. The health of the St. Johns River is one of the most devastating, said St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman.

Spring Hill holding naming contest for new sludge-hauling trailers

Spring Hill, TN (9 Jan 2026) - You’ve heard of community-named snowplows, streetsweepers and trash trucks. Spring Hill is now looking for four names for the city’s new sludge-hauling trailers at the Spring Hill Wastewater Plant. The city is hosting a “Name-A-Trailer” contest to find the four best sludge truck names. The competition is open to all residents within the Spring Hill city limits, according to a city spokesperson. Winners will receive a prize.

Santee Water Plant To Turn Sludge Into Power In $32 Million Push

SanDiego, CA (9 Jan 2026) - In East County, the crew behind the Advanced Water Purification program is getting ready to flip the script on what goes in the trash and what powers your tap. The East County Advanced Water Purification Joint Powers Authority is moving ahead with a biopower facility in Santee that will turn organic waste into renewable electricity to help run its new water plant.

DEQ releases data from preliminary study of PFAS in biosolids, wastewater

Raleigh, NC (12 Jan 2026) - The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Resource (DWR) has released data from a preliminary study that found per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) present in soil, wastewater and biosolids, the nutrient-rich organic material after wastewater has been treated. The study is the agency’s first investigation assessing PFAS concentrations in biosolids across the state.

First state study of PFAS in biosolids finds presence statewide

Internationally

From urban waste to sustainable batteries: the innovation from Spain with sewage sludge

Buenos Aires, Argentina (25 Nov 2025) - Researchers from the Chemical Institute for Energy and the Environment (IQUEMA) at the University of Córdoba (Spain) have developed a method to produce activated carbon from sewage sludge, an abundant and difficult-to-manage waste. In Spain, around one million dry tons of this waste are generated each year, making this innovation a double solution: valorizing urban waste and creating a strategic resource for the energy transition.

Cornwall’s landfill life extended to 2047

Cornwall, Ontario, Canada (27 Nov 2025) - Cornwall’s landfill is expected to remain in operation until 2047, six years longer than previously projected, thanks to new waste diversion measures launched in 2025. Council was informed on November 10 that the clear bag policy, green bin organics program, and biosolids diversion have made a significant impact, pushing the landfill’s projected closure from 2041 to 2047.

The City That Turns Human Waste into Clean Fuel

Mannheim, Germany (27 Nov 2025) - Every time somebody flushes a toilet in Mannheim, they contribute to ecological shipping. Since March 2025, the German city’s wastewater treatment plant has been feeding an experiment of global relevance: Transforming sewage gases into green methanol, a cleaner, nearly-carbon-neutral alternative to heavy fuel oil. The pilot, known as Mannheim 001, is the first full case study of how human waste can be captured, processed and converted into fuel powerful enough to propel cargo ships across oceans. “It’s the first time the entire value chain — from sewage to finished methanol — has been demonstrated,” says David Strittmatter, co-founder of Icodos, the start-up behind the project.

Italy’s first biogas-powered heating and cooling plant opens in Peschiera Borromeo

Peschiera Borromeo, Italy (27 Nov 2025) - Italy has inaugurated its first integrated district heating and cooling system powered entirely by biogas generated from sewage sludge, marking a significant step toward large-scale circular energy models. The project, located in Peschiera Borromeo near Milan, leverages anaerobic digestion processes to convert sludge into biogas, which is then used to produce both heat and chilled water. The facility, developed by CAP Evolution, sets a national technological precedent and contributes directly to Gruppo CAP’s long-term decarbonization targets.

Sewer to furnace: How wastewater sludge is greening steel production

Dublin, Ireland (28 Nov 2025) - What comes out of our wastewater treatment plants may not be very appealing, but the real problem is what is left behind after water treatment. Wastewater plants produce a liquid sludge that is usually dried and then burnt or dumped. This is costly, polluting, and has long been considered wasteful. A group of EU-funded researchers see it differently. This sludge, they argue, could become an unlikely ally in the fight against climate change – a feedstock for producing the hydrogen and carbon needed to make greener steel. Chiaramonti is leading an EU-funded research initiative called H2STEEL that brings together academics and steel industry experts from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK. Their goal is to design a process to extract the useful materials from wastewater sludge so that they can be reused and help reduce the steel industry’s emissions.

Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant Is a Better Option Than Sewerage System: Secretary-General Chaudhary

Kathmandu, Nepal (29 Nov 2025) - Narulal Chaudhary, Secretary-General of the Municipal Association of Nepal (MuAN), has said that a Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant (FSTP) is a better option than a sewerage system for the proper management of human excreta. Speaking at the 20th meeting of the Citywide Inclusive Sanitation Alliance Nepal (CWISAN), he said that based on the resources available at the local government level, FSTPs can be operated and regulated more easily and at a lower cost compared to sewerage systems, making them the best choice for faecal sludge management.

Chuncheon City to Improve Sewage Plant Sludge Process... Annual Budget Savings of 600 Million Won Expected

Chuncheon City, South Korea (30 Nov 2025) - High-concentration return water generated during the sewage treatment process has been identified as a major factor increasing the load on the water treatment system. In particular, the Chuncheon Public Sewage Treatment Plant has faced significant challenges in handling influent sewage with concentrations (BOD) exceeding the design specification by 40%.

Mayor Aki-Sawyerr speaks at AIB Sustainability Conference 2025

Freetown, Sierra Leone (29 Nov 2025) - “On Thursday, at AIB’s Sustainability Conference I was pleased to share how through multi stakeholder collaboration, a liquid waste solution has evolved into a clean cooking solution that will soon be available for sale to Freetonians. The briquettes from the Kingtom Faecal Sludge Treatment plant will reduce demand for charcoal and should therefore reduce deforestation.” Said Mayor Aki-Sawyerr.

How DBL Ceramics Turned Waste Sludge Into Chalk for Schools in Bangladesh

Dhaka, Bangladesh (3 Dec 2025) - Earlier this year, DBL Ceramics launched its “TileChalk” initiative in collaboration with POP5, converting residue sludge from its water recycling process into classroom chalk for underserved schools across Bangladesh. The company has operated with a sustainability focus, using water treatment plants that recycle all wastewater and applying zero-waste manufacturing practices. During water recycling at its ceramics plant, DBL found that a type of residue sludge remained that could not be discharged into landfills without risking soil and water contamination.

More than 520 chemicals found in English soil, including long-banned medical substances

London, England (3 Dec 2025) - More than 520 chemicals have been found in English soils, including pharmaceutical products and toxins that were banned decades ago, because of the practice of spreading human waste to fertilise arable land. Research by scientists at the University of Leeds, published as a preprint in the Journal of Hazardous Materials, found a worrying array of chemicals in English soils. Close to half (46.4%) of the pharmaceutical substances detected had not been reported in previous global monitoring campaigns.

'No reports of fish mortalities' following leak into River Lee from water treatment plant

Cork, Ireland (7 Dec 2025) - There were no reports of any fish kills as a result of the accidental discharge of an estimated 100 cubic metres of sludge into the River Lee from a treatment plant at Inniscarra, Co Cork, according to a report by the State environmental watchdog. An audit by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of the incident, which occurred on October 15, revealed that turbidity levels — a measure of the cloudiness of the water caused by suspended particles — as a result of the discharge of the sludge were up to 100 times the recommended level.

Sewage sludge on farms under scrutiny as poll backs water firm accountability

West Yorkshire, England (16 Dec 2025) - Public pressure is mounting on ministers and water companies over the use of sewage sludge on farmland, after new polling revealed overwhelming support for tougher controls amid growing concern about pollution, food safety and river health. A YouGov survey commissioned by River Action found that 92% of people in the UK believe water companies should have responsibility for ensuring that sewage sludge spread on farmland is not contaminated, with almost nine in 10 saying the government should also be accountable.

Sechelt renews biosolids service agreement with Salish Soils

Sechelt, British Columbia, Canada (18 Dec 2025) - The District of Sechelt has renewed its biosolids processing service agreement with Salish Soils Inc. for four years, beginning Jan. 31 through Dec. 31, 2029. The contract includes an annual inflationary increase of $5 per tonne per year, making it $195/tonne for 2026, $200 for 2027, $205 for 2028 and $210 for 2029. Biosolids are wastewater treatment residuals, separated from the liquids, that contain nutrients and organic matter, Meghan Lee, director of engineering and operations and Christine Miller, manager of wastewater for the district, explained in a report to council. When this material is properly composted, it can be used for fertilizer and soil amendment.

Sustainable fertiliser made out of sewage sludge ash

Breisgau, Germany (19 Dec 2025) - How can the plant nutrient phosphorus be recovered from sewage sludge ash and used sustainably in regional organic farming? This is being analysed by the research project ‘PHÖNIX – Phosphorus recycling fertilisers in organic farming: Sustainable integration and circular economy with P-XTRACT’. The project is led by Dr Peter Hajek, plant ecologist at the Institute of Biology II/III, and Prof. Philipp Kurz from the Institute of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry at the University of Freiburg. The Freiburg Materials Research Centre (FMF) is responsible for project administration and special investigation methods.

Norfolk completes environmental assessment for upgrades to Simcoe wastewater treatment plant

Norfolk County, Ontario, Canada (30 Dec 2025) - Norfolk County has completed a Schedule B Municipal Class Environmental Assessment for proposed upgrades to the Simcoe wastewater treatment plant. The Norfolk County Integrated Sustainable Master Plan, finalized in September 2016, identified upgrades to the Simcoe wastewater treatment plant’s biosolids handling processes, including the use of biosolids storage tanks to store biosolids from the Port Dover and Port Rowan plants, based on a planning horizon to 2041.

‘Sewage sludge’ found in drinking water; dozens of families affected with stomachache, diarrhoea: Report

Bangalore, India (4 Jan 2026) - Earlier, residents believed the sickness was caused by food poisoning or a seasonal illness. This week, they noticed foul-smelling, frothy water. They discovered thick sludge from sewage inside underground sumps. One resident reported that the sump contained foul-smelling sewage, not just dirty water. They have urged BWSSB to immediately identify the source of contamination. They have also urged the authorities to restore safe drinking water. |

|

January 2026 - Sally Brown Research Library & Commentary

Provided for consideration to MABA members by

Sally Brown, PhD., University of Washington

A sticky mess

New Year; back to business. These days when you work with biosolids, back to business means back to PFAS. I titled this library ‘A sticky mess’ because that is what the whole thing is. Despite the claims of ‘no stick’ PFAS in biosolids just won’t go away. Take article number 1: EPA: Superfund cleanup ‘likely’ fouled Pennsylvania town’s water for an example. The last library focused on how well biosolids were able to restore heavily metal contaminated soils. The mountain at Palmerton, PA was the first to clearly demonstrate this. Heavily contaminated with lead, zinc, cadmium to name a few, the mountain had been barren for decades with the metal rich soil eroding into the creek. A mixture of biosolids and fly ash (a lime rich residual) greened it right up. The site is still green – no complaints there. But now the residents have PFAS in their well water and the finger is pointing straight to the biosolids. This is an article from a journal associated with Politico. I also looked at the EPA report - not clear to me that biosolids were the source. The site was reclaimed in the 1990s with biosolids from Allentown, PA. Allentown is a rust belt city with no clear industrial sources - but the point here is finger pointing, not the necessary detective work to determine if the headline has any merit in reality. Just for a point of reference, here is Palmerton BEFORE the biosolids:

In the article, the authors note that the PFOA and PFOS in the well water measured as high as about 60 ppt. In the EPA report they also report that some measures were below the current regulatory limits (4 ppt). That brings us to article #2 What Limits Will the World Health Organization Recommend for PFOA and PFOS in Drinking Water?. The article points out that the initial recommendation (issued in 2022) was 100 ppt each for PFOS and PFOA. The authors argue that these limits are way too high and note that limits elsewhere are lower:

• Denmark 2 ppt

• Canada 30 ppt (for total PFAS)

The WHO noted when setting their proposed guidance that there is too much uncertainty about what concentrations are potentially hazardous. The authors here suggest that other studies do make that clear. WHO based their limits on what was technologically feasible rather than using health based numbers. Here the authors disagree. The point of my including this is to show that what is safe is a really good question. The water in Palmerton would have been just fine by US standards in 2016. How sure are we that 4 ppt is a solid number and truly different from 40 ppt?

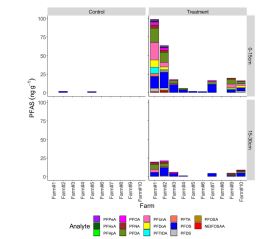

Article #3 Quantification of PFAS in soils treated with biosolids in ten northeastern US farms is a survey paper in a very well respected journal. It reports on PFAS concentrations on biosolids amended farm fields in PA, same state as that Superfund site from paper #1. The authors as farmers for the total number of biosolids applications and the application rate - here reported as wet tons per ha per yr. Two of the farms sampled with biosolids coming from a private company had much higher PFAS concentrations in the surface soils than the others. The loading rate for the first with 4 total applications was unknown and the 2nd had two applications per year of 6 wet tons per acre over 18 years. Note that farm #7 started getting biosolids 2x per year in 1996 with the last application in 2022.

To have made that much of an increase with minimal loadings strongly suggests industrially contaminated materials and shows that MI is doing it right. Either that or the farmers weren’t remembering exactly quite right. Note much lower concentrations in the lower horizon. Also note that the farm with the potentially highest cumulative loading did not have particularly memorable PFAS concentrations. The authors conclude that biosolids can be a significant source of PFAS. They do not say that the sky is falling in PA but I would suggest carrying an umbrella if you happen to be heading that way.

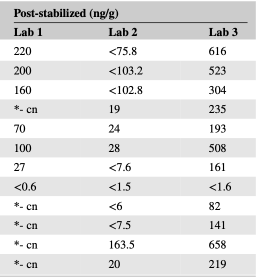

Paper #4 Surveillance of PFAS in sludge and biosolids at 12 water resource recovery facilities presents results from sludge and biosolids samples collected from 12 different plants across the US and analyzed by two university research laboratories and one commercial lab. They use the almost final version of Method 1633 as well as a modified version of EPA SW846. The point of this article is not to say that the sky is falling. Rather it is to say that the number you get depends on the lab that you use. Take the results from 5:3 FTCA – likely the worst as it was the one that they showed, but still. Each row represents a different biosolids sample. The results vary by hundreds of parts per billion. It is a shame you’re thinking that the authors kept the labs anonymous. Otherwise Lab #2 would be seeing a big spike in samples.

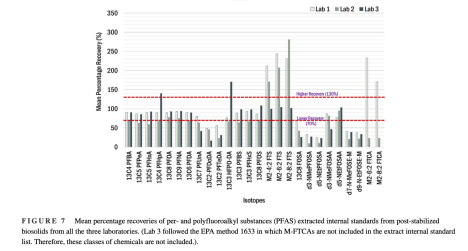

The variability was much lower for PFOA and PFOS. You can see that in the figure below. It shows how well each lab recovered added internal standards for the different PFAS compounds. Ideally you want to recover 100% of what you add. For these complex chemicals at such low concentrations, the standards are much lower. The authors show a range of 70-130% recovery. That means that for these compounds a concentration of 10 ppb really means that the concentration with good recovery is 7-13 ppb.

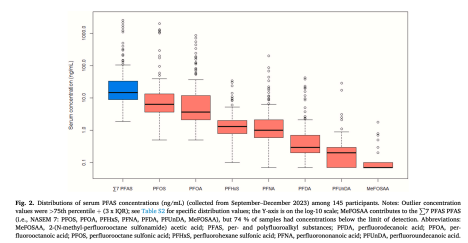

One could argue that Paper #5 Concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in private well drinking water and serum of individuals exposed to PFAS through biosolids: The Maine Biosolids Study makes the situation even more of a mess. This is a critical study (thanks Andrew Carpenter!) that takes us to Ground Zero for PFAS and biosolids and explores the connection between PFAS in the amended soils and PFAS in the blood for residents who drink well water. The authors start by noting that at the most contaminated sites in ME, the geometric mean PFOA and PFOS concentrations in well water were 1749 and 887 ng L (ppt). Blood concentrations were very high - 116 and 58 ppt for PFOA and PFOS. Those concentrations are clearly not acceptable. This study focused on people living near or on fields with long term biosolids applications. They sampled people’s blood and used data from the state on well water PFAS concentrations. Any of the study participants whose well water had exceeded MEs’ limits of the sum of 20 ppt of the top 6 compounds, had had filters installed.

This is not a simple study and the results are also not so simple. People don’t drink the same amount of water, some here claimed to only drink bottled. Others claimed to drink gallons each day. There is no information on the biosolids - loading rates or soil PFAS concentrations.

The authors do say that the biosolids were PFAS contaminated but don’t specify what counts as contaminated. The PFAS in the well water in the study had mean concentrations of the 6 regulated compounds of 26 ng L versus the 4.3 ng L in the population that was eligible for the study (meaning they also lived near biosolids application sites) but didn’t take part. Both groups were similarly distant from biosolids application sites. Well water concentrations had a mean value of 13.6 ppt PFOA and 3.6 ppt PFOS. Here is what the blood concentrations looked like (note that it is a log scale graph).

The kicker here is while the authors found a strong correlation between the water PFOA concentrations and blood PFOA concentrations - the other correlations were weaker. Leading them to conclude that other sources/ exposure pathways were to blame.

What to take from all of this? My recommendation is source control. If the PFAS coming into your plant and ending up in your biosolids is coming from homes rather than factories - it is really hard to point the finger at the biosolids. That and this picture are the closest things to cleaning up the mess that I can manage. Happy new year.

Sally Brown is a Research Associate Professor at the University of Washington, and she is also a columnist and editorial board member for BioCycle magazine.

Do you have information or research to share with MABA members? Looking for other research focus or ideas?

Contact Mary Baker at [email protected] or 845-901-7905. |

|