|

May 2025 - MABA Biosolids Spotlight

Provided to MABA members by Bill Toffey, Effluential Synergies, LLC

SPOTLIGHT on Young Professionals in the MABA Region

Ryan Chewinski

“I have visited a farm, looked around, and seen a slice of Heaven.” Ryan Cherwinski says this of his joy in working with the farming community to line up land application sites for biosolids. Ryan is a “relationship person,” and sees his work with the Mid-Atlantic region of Denali Water Solutions as an opportunity to provide genuine value to farmers stressed by high costs of fertilizers and by low prices for their products. He works as a regional manager in Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. This position allows him to witness an “instant reaction” in crops and to aid the farmer’s land stewardship of his land, providing services that are of significant help. He doesn’t see himself doing anything else, as he values his relationship with the landowners and he enjoys facing new challenges every day.

After graduating Bloomfield University, Ryan moved to the Northumberland County Conservation District and then Dauphin County District, serving as an agricultural conservation technician. He has been with Denali since February 2021 and resides in Dauphin with his wife and their three-month-old daughter.

Ryan is an outdoors guy, with a love of fishing and hunting, and he is grateful for a job that allows him a lot of outdoor time.

He enjoys being of service to farmers. He tries to take off their plate the time and cost of managing nutrients, a service that includes providing spreading equipment and low-impact vertical tillage. As was the case as a Conservation District employee, he values the lasting relationships with farmers, each of whom is unique. As most of the farmers have adopted no-till cultivation practices, the customary cycle for surface application of biosolids is three years, applied to mostly field corn crops, either before planting or after harvest. This cycle allows for avoidance of excessive buildup of phosphorus. For some farms, Denali can deliver alum sludge from public water filtration systems, and the alum helps to bind up phosphorus to reduce release to the waters. Ryan has moved into this role of regional manager with the valuable support of his Denali colleagues, notably Tommy Baro for field operations and Stefan Weaver for regulatory steps.

While much of his work time has him with farmers, mine reclamation has been his favorite project. He recalls visiting a previous project site after a midwinter snowfall and witnessing a majestic herd of elk grazing the land. He has seen an abundance of turkeys, geese and mammals reoccupy lands that had been disturbed by mining in the bituminous coal region, and he is motivated by the many thousands of disturbed landscapes across the state. Where Baro and Weaver have been Ryan’s farm specialist, in mine country this advisor role is Greg Barchey’s to play. Denali deploys a portable unit for blending biosolids with lime to achieve stabilization and liming, and Barchey was a key part of the team that designed it and got regulatory approval. Portability allows the unit to be placed conveniently after mine closure activities have placed overburden over the rock. But this region has poor soils and natural soil as a final cover is scarce, so Ryan deploys large chisel plows and disc harrows to make several passes over the surface layer onto which the allowable 60 dry tons of biosolids, together with the lime amendment, have been placed. In some cases, the disturbed lands are owned by hunting clubs, and seed mixes can be tailored to landowner requests. Ryan says the results are infallibly amazing, in stark contrast to the meager growth on mine sites treated with conventional fertilizer and hydroseeding, and relationships with the mining companies are understandably strong. Ryan has developed a good working relationship with the region mining office of the Pennsylvania DEP that reviews sites for biosolids use, and attributes that relationship to the “visuals” of a strong vegetative cover.

Ryan Chewinski conferring with a Denali colleague at a mine reclamation site in Pennsylvania

Ryan says of his work, “I may be delusional, but I believe our service to the farmers, my willingness to champion biosolids to any and everyone, gain public support. I talk about how we take a waste and turn moonscapes into meadows… it is a miracle.”

Mikayla Regan

Mikayla’s enthusiasm for her work at Northern Lancaster County Authority is clear and palpable. Her LinkedIn profile proclaims: “I am a dedicated and passionate water and wastewater professional.” That is very clear.

If Mikayla’s energetic enthusiasm for our profession evokes an image of a team of kids playing field hockey, well that is because field hockey coaching is very nearly a second career. Ice hockey is close to field hockey as a favorite sport.

Mikayla is a proud graduate of Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. While attending the two-year Water and Environmental Technology program, she worked full-time as a drinking water operator at Red Lion Municipal Authority’s 3.5 MGD treatment facility. Her combined experiences prepared her to join Arro Consulting in the position of a circuit rider for a diverse caseload of different small to medium drinking water and/or wastewater treatment facilities spanning over 15 counties in the state. In this role, she saw and did it all – carrying out day-to-day operations, ordering chemicals and supplies, providing preventative maintenance, testing influent and effluent, responding to inclement weather, carrying out PA OneCalls, installing and reading meters and conducting inspections with DEP.

This expansive role could not contain Mikayla. She entered the consultant side of the profession with Material Matters in Elizabethtown, PA, a firm specializing in optimizing residuals treatment and utilization. With the support of her mentors, Mikayla emboldened her interest and involvement in the beneficial use of biosolids. And then she made her move to Northern Lancaster County Authority in Denver, Pennsylvania, a utility with an average daily flow of 400,000 gallons, where she now joins a team of 4 operators, one office administrator, and, in her words, “a great board.”

Northern Lancaster merges Mikayla’s wastewater and operations skills with her coaching skills. She helps train new operators and is the point person for the internship program with Thaddeus Stevens. She helps lead the biosolids beneficial use program, focusing on continued improvement, proactivity, and resiliency. In addition, Mikayla leads plant tours and is happy to spearhead a new internship program with her alma mater, Thaddeus Stevens. She hopes to help develop a stronger workforce, to emphasize the importance of beneficial use, and to encourage new operators. She also draws upon her communications skills to reach out to the public on environmental issues of the day, such as PFAS, and solicits public support for reducing nuisances that flows in the influent from the authority’s large waste watershed items such as rags, fibers wipes, personal waste items and persistent pollutants.

Mikayla is very mindful, too, as a lifelong resident of central Pennsylvania, of the virtues of frugality and self-reliance. She did not shy away from challenging the recommendation by the Authority’s engineer to landfill over 1,000 wet tons of biosolids in lieu of beneficial use for this summer’s reed bed excavation project. Northern Lancaster utilizes four reed beds to dewater aerobically digested solids and produces Class B biosolids. Each bed has 10 cells that are 25 feet by 50 feet in dimension and 6 feet in depth. All but one of the beds has had their original aggregate and sand media replaced with crushed, recycled glass. Recognizing the increasing challenges and expenses of small facilities faced with landfill disposal while keeping in mind concerns over PFAS, Mikayla successfully advocated for the Authority to screen their influent, effluent, biosolids, and reed trimmings for PFAS, and to continue to pursue beneficial use where applicable. The current enthusiasm for PFAS has the staff sampling each of the beds in turn, to establish whether the existing media and the reeds that grow in it can be recycled to land, or, instead, the media needs to be taken to be disposed of due to contamination. Annually, Northern Lancaster produces up to 100 dry tons of residuals for stabilization in the beds, where time and reed growth has resulted in a cakey, soil-like material infused with dry reeds. Sampling of the reed bed solids has demonstrated biosolids quality is suitable for mine reclamation.

Mikayla Regan is holding a tool unofficially called the “poop scoop” which is used for inspecting reed bed loading and growth at the Northern Lancaster County Authority plant in Denver, Pennsylvania.

Mikayla speaks enthusiastically about her role as a champion of clean water to her customers. She is eager to face the PFAS issue head on, and she has made the case with her colleagues at small plants across the state that they should be in communication with customers on the issue of “forever chemicals,” in part because unreasonable fears may cause the public to insist on expensive agency actions.

If you want to catch Mikayla’s energy, she invites folks to seek her out at the MABA Summer Symposium, July 8 through 10th in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania.

Danielle Sheahan

“You ought to be an engineer,” Danielle Sheahan’s science teacher advised her as a Junior high student. Her first thought was railroading, of course, but this laid-back science teacher, retired from Anheuser-Busch who had turned to teaching for fun at Danielle’s Missouri high school, got his point across. When she landed at Missouri Science and Tech College, she flipped through the engineering majors, and environmental engineering jumped out at her, perhaps in part because this major had the fewest number of students. But from her very first class; she liked what she heard, and she heard a lot about wastewater and biosolids. The environmental program at this technical college included assisting wastewater research, and in Danielle’s case this included characterizing extracellular polymeric substances in laboratory reactors. Her college internship experience included modeling combined sewer overflows for a midWest city, participating in a conceptual master plan for a California utility, and developing safety protocols for a BeyondZero safety team.

Now a dozen years since she started environmental engineering, Danielle can say with enthusiasm, “Anaerobic digesters are cool, really cool!” And, indeed, Danielle is steeped at this moment on authoring a technical memorandum on digester cover performance for a client she will not name. Soon, she will be turning her sights on a digester system owned by a Utah agency that is considering refurbishment.

Brown & Caldwell was Danielle’s first employer out of college seven years ago, though she had an internship with Jacob in her last year of college. She works from home in Germantown, Maryland, in a national team at Brown & Caldwell that provides design services for the company. As Process Mechanical Engineer, Danielle gets to work on projects in all corners of the United States, for whatever component of wastewater her skills are needed. One project was a digester project in the South, and a second was a biosolids dryer project in New England. She also has had the fun of being part of a team bringing the EcoRemedy gasifier system to the Derry Township Municipal Authority in Hershey, Pennsylvania. She has had a key role in the design of pumps and conveyors; she will be watching to see if her designs for a cooling conveyor will be needed.

Danielle Sheahan taking a pause between digester design projects for Brown & Caldwell

The home office work suits Danielle. She met her future husband at a professional conference in Missouri, but his job took him to Washington, DC, so it was convenient to relocate. With a firm as broadly based as Brown & Caldwell, Danielle can turn to mentors such as Ted Hull in Atlanta and Tom Chapman in California.

We at the Mid Atlantic Biosolids Association can expect to hear from Danielle in the future, and not only because of her enthusiasm for wastewater and digestion. While still a student in Missouri Danielle completed the Competent Leadership program offered by Jacobs P3 Toastmasters Club.

Xiao Guo

“I like building things, that has been a consistent theme in my life. I even assembled my own PC, because I wanted to understand how the components worked together.” Xiao is eight years out of completing her engineering degree at the University of Delaware. Over these few years, first with Hazen and now with Carollo, Xiao has evolved into a professional engineer with a specialization in biosolids processes, including design of digesters, dewatering equipment, conveyors and cake storage. She is very close now to seeing a project from design concept all the way to installation: “it will be extremely satisfying to watch it come to life.”

Now 30 years old and living in the District of Columbia, Xiao was raised in suburban Boston with her brother. Xiao is proud of the high standard for hard work set by her mother, who had emigrated from China to attend college at the University of Georgia and who from there followed a steady professional trajectory from bank teller to a bank vice president. Xiao credits Delaware’s environmental engineering program for exceptional preparation, particularly in preparing her for the professional engineering exam. She also credits her career to great mentorship from some of the top biosolids engineers in the region, names familiar to the MABA community, such as Rashi Gupta, Paul Bassette, Matt Van Horne, and Paul Knowles.

Her enthusiasm for creating big things in biosolids was cemented by her early assignment to participate in the significant wastewater design projects. One of her first projects was the expansion of dewatering and thickening processes using centrifuges, where she was able to learn the design process from start to finish. She was then on a team that implemented a new chopper pump and jet mixing system for digesters for a plant located in Suffolk, VA. She recently completed a comprehensive review of digester mixing technologies for a California agency, which is currently in design, and has made recent professional presentations on that work.

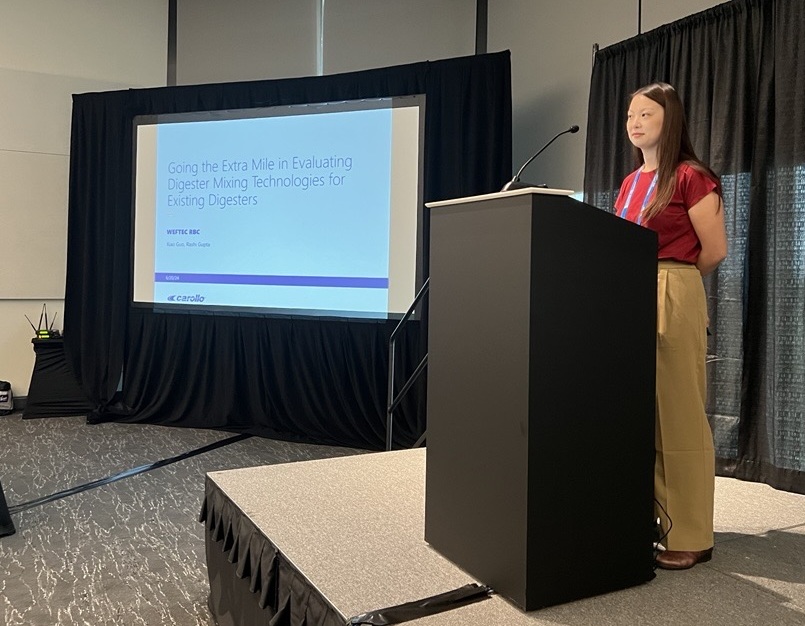

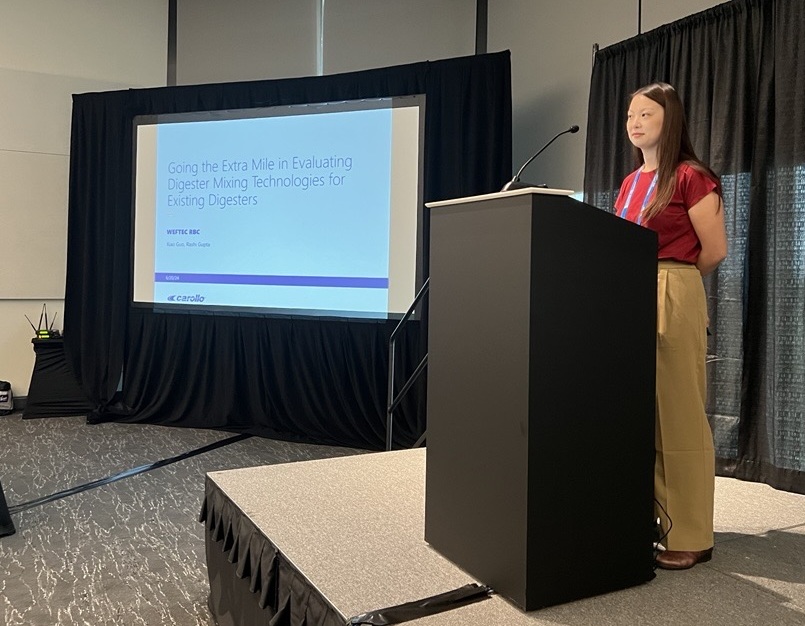

Xiao Guo is presenting on the variety of mixing pump technologies for anaerobic digesters on a project for a California agency with Carollo Engineers.

Xiao is primarily concerned with PFAS and microplastics in our water, and is interested in viable approaches to treat these pollutants. She is particularly interested in how we can use microorganisms to degrade plastics, similar to how we use microorganisms to remove pollutants like nitrogen from wastewater now. But when speaking with people of her generation, she can get frustrated by an apparent disconnect between environmental issues and water infrastructure. “They definitely have a passion for solving environmental issues and making the world a better place for future generations. But I feel there is a connection to critical infrastructure and its role in public health that is missing. We need to reach the young people and get them interested in using their talents to make and maintain clean water.”

To balance her inherited tendency to be a workaholic, Xiao turns to several activities. She has been a long-standing video gamer and keeps her Nintendo Switch console close at hand. Having taken art lessons as a child, at first reluctantly at her mother’s suggestion, Xiao paints with oil and acrylics as an adult, an act of meditative value. Xiao also likes to watch documentaries and learn more about the world around her by traveling when she is able. Other smaller hobbies include doing her own nails, watching movies, and enjoying time with friends. Another downtime activity is watching D-I-Y videos, which Xiao regularly marks for future reference for when she has a home of her own. After all, Xiao loves knowing how to create things, things as small as a painting and things as big as a wastewater plant. That is precisely the kind of engineer we all need in our biosolids profession.

For more information, contact Mary Baker at [email protected] or 845-901-7905. |

|

|

April 2025 - MABA Biosolids Spotlight

Provided to MABA members by Bill Toffey, Effluential Synergies, LLC

SPOTLIGHT on Two New York Plants – Watertown and Endicott

“Ingenuity, that is a good word for it,” agreed Angel French, Plant Manager of the Watertown Water Resource Recovery Facility. Unfazed by unconventional and innovative technologies, French encourages her operators and maintenance staff to apply ingenuity as a team to “make it all work” in the face of unexpected challenges. French explains, although Watertown’s WPCP is classified by NYS regulations as a large plant, with a design daily flow of 16 MGD, and an average daily flow of 10 MGD, compared to Buffalo, Syracuse and Rochester and those in metro New York, Watertown is on the small end of the spectrum. At this size, French rotates operators across all processes, and the maintenance staff are licensed operators, fostering an ethic of teamwork that is able to apply ingenuity when new equipment stumbles on startup.

This Google Earth view of the Watertown Water Resource Recovery Facility, located in the northern reach of New York State, underscores the proximity of a major recreational facility to the south, and the cake storage area converted from a former lagoon rebuilt north of the digesters.

Ingenuity enabled Watertown to pivot in 2017 when new federal Sewage Sludge Incinerator regulations compelled the city to end incineration. Because sludge ash had been disposed of at solid waste landfills, Watertown was initially able to divert from incinerators to landfill disposal of cake for its management option. Dewatering equipment at Watertown is also unusual, representing one of a handful of plants in the MABA region with plate-and-frame presses. The discipline of maintaining good solids content, targeted at 20 percent solids, for incinerator feed was no less necessary for landfill disposal. But tipping fees drove Watertown to pivot again from landfill disposal to land application. This pivot required it to demonstrate that processes met the Class B standards through three anaerobic digesters, operating in series to achieve minimum hydraulic retention time.

Land application is a challenge in this far reach of New York State, as the season for application is narrow, requiring the facility to develop capacity for on-site storage over the winter. Storage is a particularly strong challenge for Watertown, as its plant adjoins actively used trails and playfields. Winter freeze and thaw cycles do not improve the quality of biosolids cake, and odors during pile disturbance is a risk factor. Watertown’s biosolids are used typically for feed crops for dairy herds, and fertilization of field corn is the dominant use. Last year, Watertown paved over its old ash lagoon, which had been shut down when incineration ceased, to increase the available space to store biosolids when cold weather makes storage necessary.

Two factors with land application have French considering management options. First, against the capital cost for a future facility for cake storage is balanced the cost of installing a biosolids dryer. A dryer would have the obvious advantage of making winter storage easier, but it would also reduce risks from odors when biosolids are moved from storage. Second is an arising concern with PFAS, both from state regulations and political responses to PFAS in New York State that include bans on land application. Dried biosolids could be better handled than cake through a thermal conversion technology that destroys PFAS.

Ingenuity at Watertown is highlighted by three features of the plant’s solids handling. The features are a low-head-loss headworks bar screen, second is a biogas fueled sludge pump system, and third is a dry polymer mix system that has been optimized for Watertown’s unique plate-and frame presses.

Hydro-Dyne Engineering is the manufacturer of bar screens recently installed on Watertown’s principal influent line. Hydro-Dyne is represented in central New York by Siewert Equipment. Watertown has deployed the Great White Center Flow Screen which is special for a design that achieves “low head loss and zero carry over” with its ¼ inch wide bars. The screen is deeply recessed in the influent well. At the outset of its operation at Watertown, the conveyor system at the discharge chute frequently tripped. While the discharge apparatus served to concentrate and dewater the screenings, the back pressure was too great for the equipment. With the ingenuity of the operators, the discharge chute was reduced in length, thereby reducing, too, the quantity of screening moved by the conveyor. The ¼ inch screen has significantly reduced inert materials passing through the plant, improving the entire process train and biosolids quality. French anticipates a capital improvement to install a similar screen on the second major influent line, the one coming from a diverse number of other interceptor lines serving outlying communities.

The Hydro-Dyne Great White bar screen was a “game changer” for Watertown for improving treatment and biosolids quality, with images here of both downstairs influent equipment and upstairs screenings discharges.

Watertown has replaced two conventional sludge pumps with Kraft Energy Systems Model KB 130P equipment, using MAN direct drive biogas fueled engines, supplied by the Kraft Power Corporation in Syracuse, New York. Biogas from the digester complex is cleaned of siloxanes and is otherwise untreated. Sulfur is not a challenge at Watertown, as the use of ferric for phosphorus removal also captures sulfides. During normal plant operations (i.e., not wet weather) one biogas fueled engine will pump 100% of plant influent flow. The use of biogas in this part of the plant provides for consistent biogas demand across the year, in contrast to use of biogas to meet heat demand of boilers and digesters.

MAN direct drive biogas engines, supplied and installed by Kraft Power in Syracuse, are close to overcoming start up challenges, and promise soon to fully meet pumping requirements on biogas during normal flows.

But installation of the engines has had its challenges. French remarks: “any new equipment at a facility has its “bugs” that need to be worked out.” At the outset of installation, controls which set variable pump speeds to the level of sludge in the tanks, were not properly calibrated. French and the control experts at Kraft puzzled over the challenge. French says: “once the controls were fine tuned for our facility, they worked amazing. …it was a Wednesday, the day before Thanksgiving, a four-day weekend. The control system company FINALLY figured it out. The relief I had walking out the door that day knowing the pumps would respond as they were designed was unimaginable.” One problem remains. Premature wear of the engine valve trains has been experienced. Frank Scalise, Sales Manager for Combined Heat & Power Systems at Kraft Power, explains that the MAN factory has a new lifter arrangement that ought to improve the situation.

Watertown’s plate-and-frame presses may seem anachronistic in today’s use of specialized presses and centrifuges, but Watertown intends to stay with them. The presses were manufactured in 1981 by Edward and Jones and were installed by engineering company Stearns & Wheler Engineers. Initial reasoning for utilizing plate and frame press was its ability to achieve higher percent solids for incineration. But the presses meet the needs for preparing biosolids for land application, though they do require close attention. Fabric filters are changed at least annually, and cast iron filter press plates have been replaced with composites. A principal focus for good control of dewatering is constant adjustment of polymer dosages. Dry polymer, delivered in 55-pound bags, is mixed carefully to deliver a 0.25% solution that meets a homegrown “swinging the bucket” test for an effective dosage. If too much polymer is used, the cake becomes sticky and does not fall onto the conveyor when plates are released. The presses operate one shift, five days weekly, though in the Spring and Fall, when small agencies in its wastewater shed clear out their basins, a second shift or a second day of dewatering can be added. The easy start and stop of this dewatering system provides good flexibility. Looking to the future, French conjectures that a change to dewatering equipment would be on top of the plate and frame, rather than a replacement for it.

Now over four decades old, Watertown’s plate-and-frame presses operate well when given special attention to polymer dosage and annual replacement of filters.

As French and her staff look for new ideas and new ways of solids handling, they are taking cues from other agencies, and one such agency is the treatment plant serving Village of Endicott, New York, led by a similarly ingenious plant manager, Philip Grayson. The Mid Atlantic Biosolids Association held its Summer Technical Symposium in Endicott in 2023, and Grayson’s plant was the destination for the tour on the second morning.

Endicott Water Pollution Control Plant, in the southern tier of New York, has enjoyed loyal compost customers in the past, and is building a market for its new biosolids product.

At the time of the Symposium, Grayson was already winding down the plant’s composting operation. The Village began in 1985 the composting of biosolids with a Taulman-Weiss in-vessel system and after 20 years of operations, it had added windrow composting to ensure complete stabilization. To reduce costs while still producing a Class A EQ product, the Village moved to biosolids drying, selecting a Gryphon Environmental’s single-pass belt dryer. As an early adopter of this technology in the MABA region, Grayson relied on the collaborative culture at Gryphon to be a team that together could meet challenges with ingenuity. One notable area were changes to the method of conditioning the feed material to the dryer belt. Gryphon previously only handled aerobically digested and not anaerobically digested material. The differences between how those two dewatered cakes are significant and created operational challenges. In addition, occasionally Endicott had issues with blinding of the inlet screens with human hair and other fibers. These two issues led to Endicott installing a Gryphon system that uses blades to shred the feed.

Endicott is an “early adopter” of Gryphon Environmental’s single pass belt dryer and has already fitted a new 10 foot module to expand processing capacity by 25 percent.

Hair and fiber are seldom a focus of attention at biosolids conferences, giving rise to the kind of challenge Gryphon has had with its dryer feeding system, one that requires ingenuity in a solution. Josh DeArmond, Gryphon’s Director of Engineering, says that a frequently invoked motto at Gryphon is: “This is NOT our fault, but it IS our problem.” In the brainstorming of solutions to a blinding by fibers of the dryer feed system, the term “harrow” was borrowed from the agricultural industry to describe a system of star-like blades for cutting through the fibers in the dryer feed. The company has this as a patent pending solution.

The second area was ensuring adequate drying time by extending the belt with an additional ten-foot module. During the early stages of dryer operation, Grayson determined that having flexibility in managing solids flows and in ensuring steady compliance with time/temperature standards warranted an additional dryer module, a fifth 10 foot drying section and a new longer belt, adding 25% to processing capacity. The challenge was fitting the new unit into a building with narrow aisles and limited dimensions. Endicott’s staff was able to shift the location of the belt filter press and conveyor, and Gryphon modified its modules construction to allow the staff to squeeze the unit in place. Ingenuity and collaboration enabled Endicott and Gryphon to together accomplish results that met the unexpected challenges of the moment.

Endicott shares several key features with French’s Watertown facility in size (Endicott serves 50,000 customers), in its anaerobic digesters and in having process equipment that utilizes the biogas. But a key common concern is the vulnerability of its planned, long-term recycling program to changes in state regulations of land application, largely a consequence of the global issue of PFAS. Gryphon Environmental’s motto applies here: PFAS is not our fault, but it is our problem. While neither agency sees a problem with results of biosolids testing for PFAS undertaken at NYS DEC’s direction, both are concerned with the potential endpoint of current political and regulatory reaction to PFAS, which may yet throw the entire recycling pathway for biosolids into question. One area of concern is that, even with a final resolution of PFAS standards in their favor, both agencies rely on willing farm customers to take their biosolids. Farmers may become wary of accepting biosolids even when their sources are better than regulatory limits, and companies servicing the farmers face emerging acceptance obstacles and challenges from local officials. This situation underscores Endicott’s interest in diversifying its outlets for dried biosolids, and in Watertown’s interest in embarking on a search for a suited dryer technology. Both French and Grayson anticipate a need to have flexible outlets for biosolids, a need that requires the ingenuity that has guided investments in each agency’s processes over the past decade. And both will have the teams within their facilities and with their equipment suppliers to meet future challenges.

Watertown and Endicott exemplify the power of teamwork to meet challenges with ingenuity.

For more information, contact Mary Baker at [email protected] or 845-901-7905. |

|